In this article, We are going to learn about Site Reliability Engineering (SRE) core terminologies. It’s important to understand those terms because they are used a lot nowadays in the software industry. I know that learning terminologies might sound boring or complex but I will try to make it simple and as practical as possible. We will use the shakespeare service explained before in part one as an example service so please make sure you check that first. It’s also important to check part2 when we talked about error budgets if you haven’t already. without further ado Let’s start with Service Level Indicators (SLIs).

SLI or Service Level Indicator

SLI or Service Level Indicator is a metric (a number) that helps us define how our service is performing, For example:

- Request Latency: how long it takes to return a response to a request.

- Error Rate: the fraction or requests with errors (e.g. an API returns 500)

- System throughput: how many requests we got per seconds

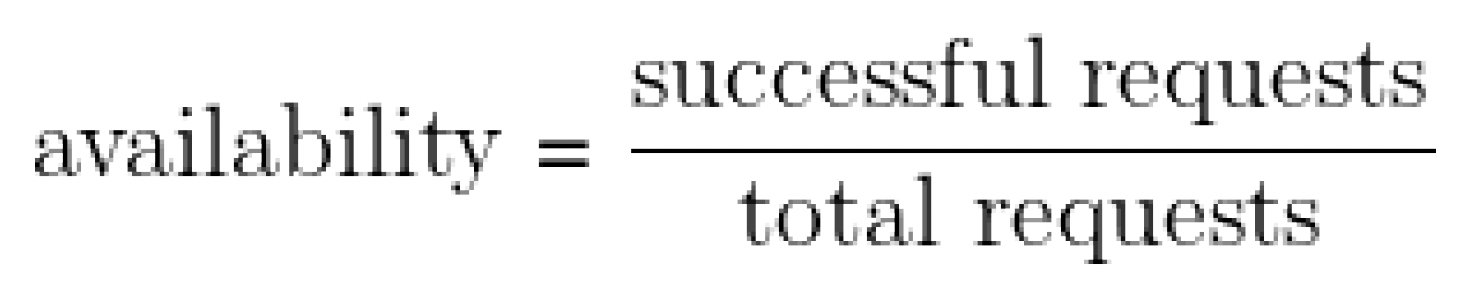

- Availability: the fraction of well-formed requests that succeed. 100% availability is impossible, near-100% availability is achievable. We express high-availability values in terms of the number of ”nines” in the availability percentage. For example, availability of 99.99% can be referred to as ”4 nines” availability.

- Durability: the likelihood that data will be retained over a long period of time. It’s important for data storage systems.

There are more metrics we can collect to give us more insight about our system health but the question here is that how can we actually identify what metrics are meaningful to our system? The answer is simple, “It depends!!”. it depends on what you and your users care about.

We shouldn’t use every metric we can track in our monitoring system as an SLI. Choosing too many indicators makes it hard to pay the right level of attention to the indicators that matter, while choosing too few may leave significant behaviors of our system unexamined. We typically find that a handful of representative indicators are enough to evaluate and reason about a system’s health. Services tend to fall into a few broad categories in terms of the SLIs they find relevant:

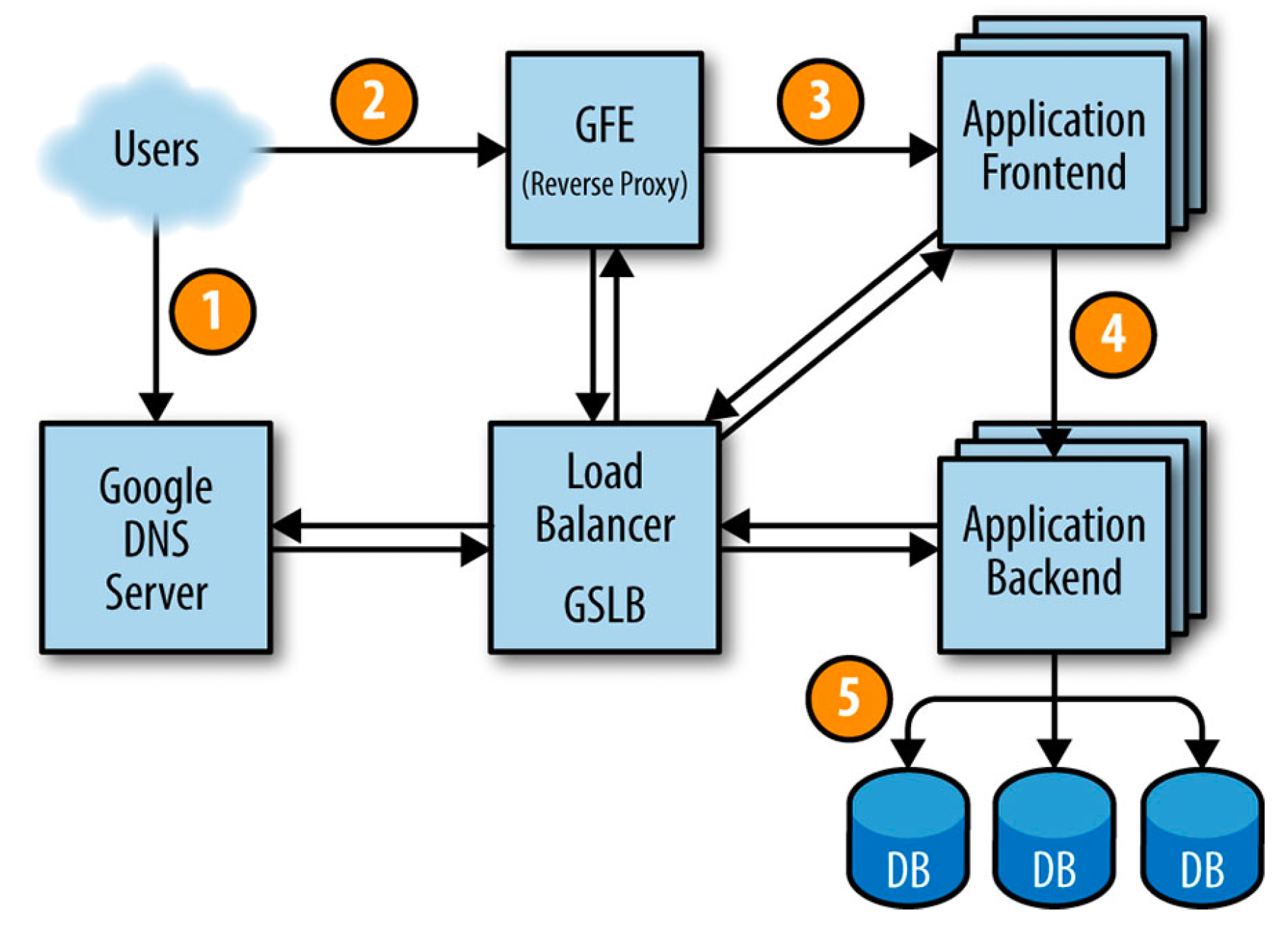

- User-facing serving systems, such as the Shakespeare search frontends, generally care about availability, latency, and throughput. In other words: Could we respond to the request? How long did it take to respond? How many requests could be handled?

- Storage systems often emphasize latency, availability, and durability. In other words: How long does it take to read or write data? Can we access the data on demand? Is the data still there when we need it?

- Big data systems, such as data processing pipelines, tend to care about throughput and end-to-end latency. In other words: How much data is being processed? How long does it take the data to progress from ingestion to completion?

To use those metrics as SLI, we need to collect and aggregate them on the server side, using a monitoring system such as Prometheus. However, some systems should be instrumented with client-side collection, because not measuring behavior at the client can miss a range of problems that affect users but don’t affect server side metrics. For example, concentrating on the response latency of the Shakespeare search backend might miss poor user latency due to problems with the page’s JavaScript: in this case, measuring how long it takes for a page to become usable in the browser is a better proxy for what the user actually experiences.

SLO or Service Level Objective

SLO or Service Level Objective is a target value or range of values for a service level that is measured by an SLI. For example, we can set the SLO for shakespare service as follows:

- average search request latency should be less than 100 milliseconds

- availability should be 99.99% which means error rate should be 0.01%

SLOs should specify how they’re measured and the conditions under which they’re valid. For instance, we might say the following:

- 99% (averaged over 1 minute) of Get requests will complete in less than 300 ms (measured across all the backend servers).

If the shape of the performance curves are important, then you can specify multiple SLO targets:

- 90% of Get requests will complete in less than 100 ms.

- 99% of Get requests will complete in less than 300 ms.

- 99.9% of Get requests will complete in less than 500 ms.

It’s both unrealistic and undesirable to insist that SLOs will be met 100% of the time: doing so can reduce the rate of innovation and deployment, require expensive, overly conservative solutions, or both. Instead, it is better to allow an error budget.

So, How can we actually choose targets (SLOs)? Here are few lessons from google that can help:

- Keep it simple. Complicated aggregations in SLIs can obscure changes to system performance, and are also harder to reason about.

- Avoid absolutes. While it’s tempting to ask for a system that can scale its load ”infinitely” without any latency increase and that is ”always” available, this requirement is unrealistic.

- Have as few SLOs as possible. Choose just enough SLOs to provide good coverage of your system’s attributes. If you can’t ever win a conversation about priorities by quoting a particular SLO, it’s probably not worth having that SLO.

- Perfection can wait. You can always refine SLO definitions and targets over time as you learn about a system’s behavior. It’s better to start with a loose target that you tighten than to choose an overly strict target that has to be relaxed when you discover it’s unattainable.

SLOs should be a major driver in prioritizing work for SREs and product developers, because they reflect what users care about. A poorly thought-out SLO can result in wasted work if a team uses extreme efforts to meet or it can result in a bad product if it is too loose.

SLA or service level agreement

SLA or service level agreement is an explicit or implicit contract with your users that includes consequences of meeting (or missing) the SLOs they contain.

SRE doesn’t typically get involved in constructing SLAs, because SLAs are closely tied to business and product decisions. SRE helps to avoid triggering the consequences of missed SLOs. They can also help to define the SLIs.

Conclusion

SLI is a metric that helps us define how our service is performing, For example the Request Latency error rate. SLO is a target value for a service level that is measured by an SLI. For example the request latency should be less than 100 milliseconds or availability should be 99.99% which means error rate should be 0.01%. SLA is an explicit or implicit contract with the users that includes consequences of meeting (or missing) the SLOs they contain.

Next, We are going to learn more about how to automate boring and repetitive tasks.